// Over the years, a half dozen research trips have taken me to a dozen of Switzerland’s 26 cantons.

Gradually, I’ve come to appreciate that, though Switzerland is a landlocked nation, lacking in natural resources, it is rich in something vanishingly rare in the rest of the world: common sense. This is most apparent in the way the Swiss get around. North America should look no farther than this alpine nation for a model of sensible, sustainable — and yes, even enjoyable — transit. It’s simply the best transportation system in the world.

This really began to sink in three years ago, when I spent a month-and-a-half in the canton of Vaud, in the French-speaking west of the country. After flying into Geneva, I rode an escalator to a railway platform located directly beneath the airport terminal. After waiting less than five minutes, I boarded a double-decker inter-city train, which featured a play area for kids, including a slide, on the upper level. Within seven minutes, we had arrived at Geneva’s main station. Twenty-seven minutes after that, I disembarked at Morges, a town on the north shore of Lac Léman, where I walked a few dozen paces to an adjoining platform, where a smaller, three-carriage electric train, run by the private rail company MBC, was already waiting. Exactly as the second-hand of the platform clock hit the top of the dial, the train pulled out of the station.

We wended our way through a landscape of grape vines and Simmental cows in their summer pastures, to the end of the line, a village with the charming name of Apples.

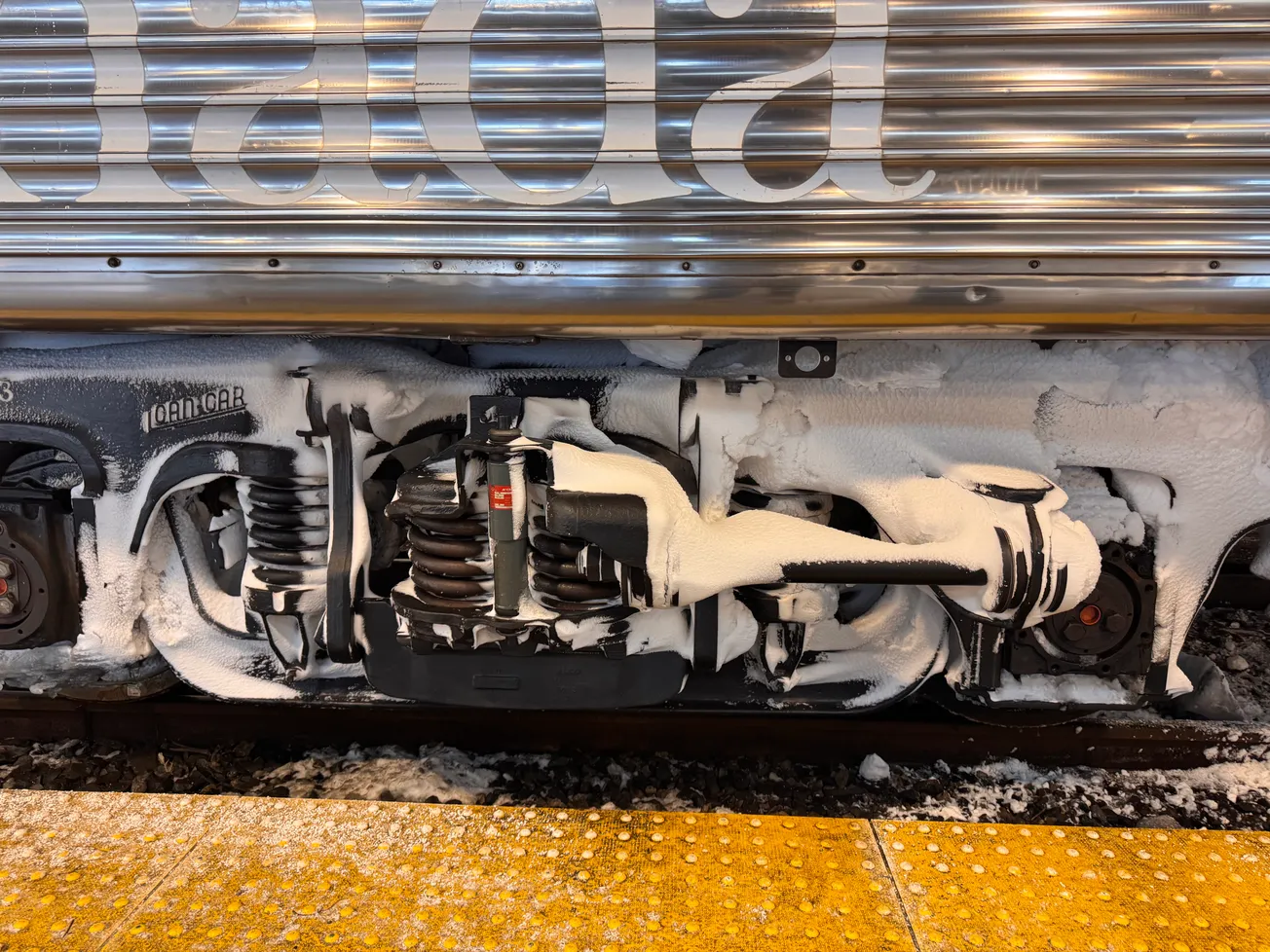

There, on the far side of a gabled stationmaster’s house, a two-carriage train was waiting for us. It only pulled away when the last of the passengers had transferred from one train to the other. We passed through four villages, spaced three to five kilometers apart, before I arrived at my stop. A short walk from the end of the open platform, a small green-and-white bus collected the disembarking passengers, which included a half dozen students returning from high school. I was whisked, along with my backpack and suitcase, uphill to my final destination, the village of Montricher (pop. 900). The entire journey went like clockwork, with one mode of transport – from heavy-hauling intercity train to that 49-passenger rural bus – meshing with the next with gear-like precision.

Fearing I’d be isolated in a small hilltop village, I’d arranged to borrow a road. As pleasant as pedalling the foothills of the Jura Mountains turned out to be, I needn’t have bothered. Any time I decided to leave the village, I could walk to the middle of the village, and take a bus back to Montricher’s rail station. Trains left hourly from six in the morning until 1:46 am. From there, I could get to larger hubs like Geneva, Lausanne, or Montreux, and travel by train all around Switzerland (and, by high-speed rail, to Italy, France, and Germany).

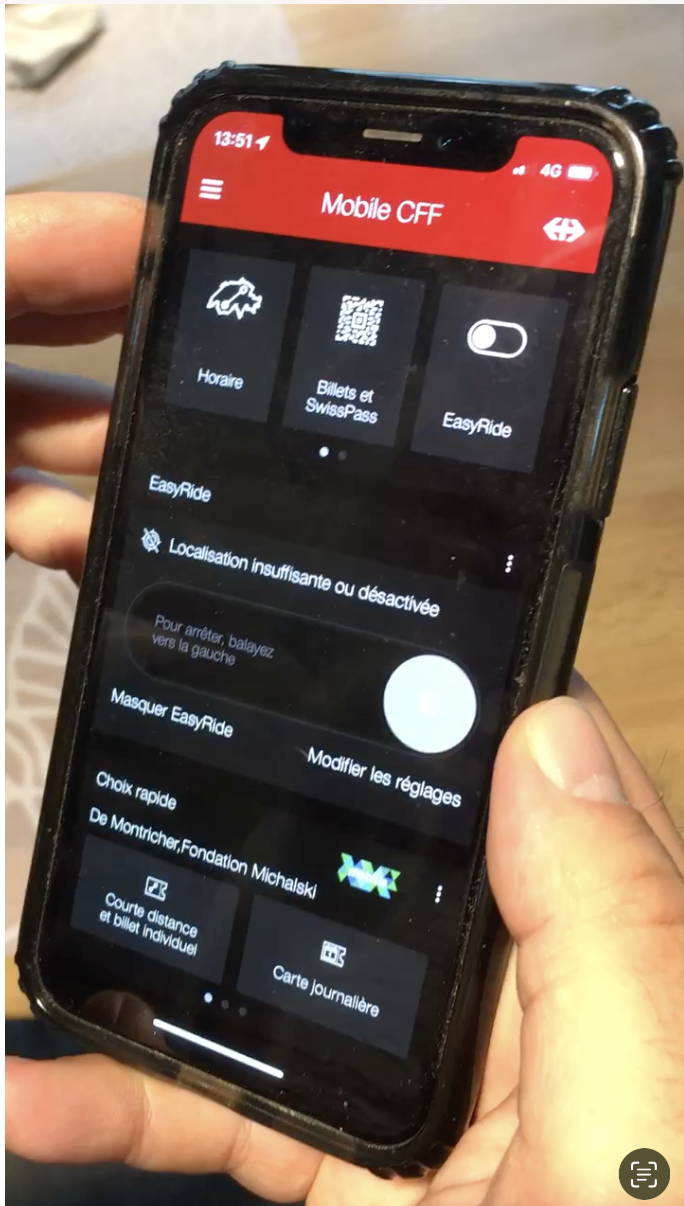

A Swiss friend suggested I download the official trip-planning app offered by SBB, Switzerland’s state-run railways. After linking it to my credit card, I was able, with a few swipes on my iPhone screen, to plan a trip anywhere in the country. This wasn’t limited to trains. SBB allows you to buy a through ticket on gondolas, river boats, funiculars, and city buses, even those run by private companies, and provides you with a QR code to show to ticket inspectors. By swiping right on the “EasyRide” tab, the app would use GPS to track my position, and automatically charge the best available fare to my account when the trip ended. (I write more about my experiences in rural Switzerland here.)

Visitors complain about the price of train tickets in Switzerland, among the highest in Europe. (One Swiss transit professional I talked to considers the high prices a “tax on tourists.”) But one can also pay a yearly subscription, currently 170 francs which gives you half-price fares on all trains. Many Swiss citizens opt for the “abonnement général,” an annual pass that, for 3995 francs, gives them free transportation on all modes, everywhere in the country. (Gondolas and cable-cars, more likely to be used by skiers, are 50 percent off.)

By federal law, every village in Switzerland with a population of more than 100 has to be served by some form of public transportation: a bus, a train, cog railway, or PostBus – the national system of mail-delivery buses which serves both cities and remote villages – on a daytime schedule of one hour or better.