The Limits of Terminal City's Transportation Evolution

// In the past two months, I've spent three weeks in Vancouver, on two separate trips. I grew up there, and my mother and sister still live in the city, so, as a general rule, I'm out there several times a year. When I was young—I lived there until my late twenties—I got around without a car, and when I visit, I rely on transit and bicycles to get around. For a number of interesting reasons, this is less of a hardship than when I was a teenager.

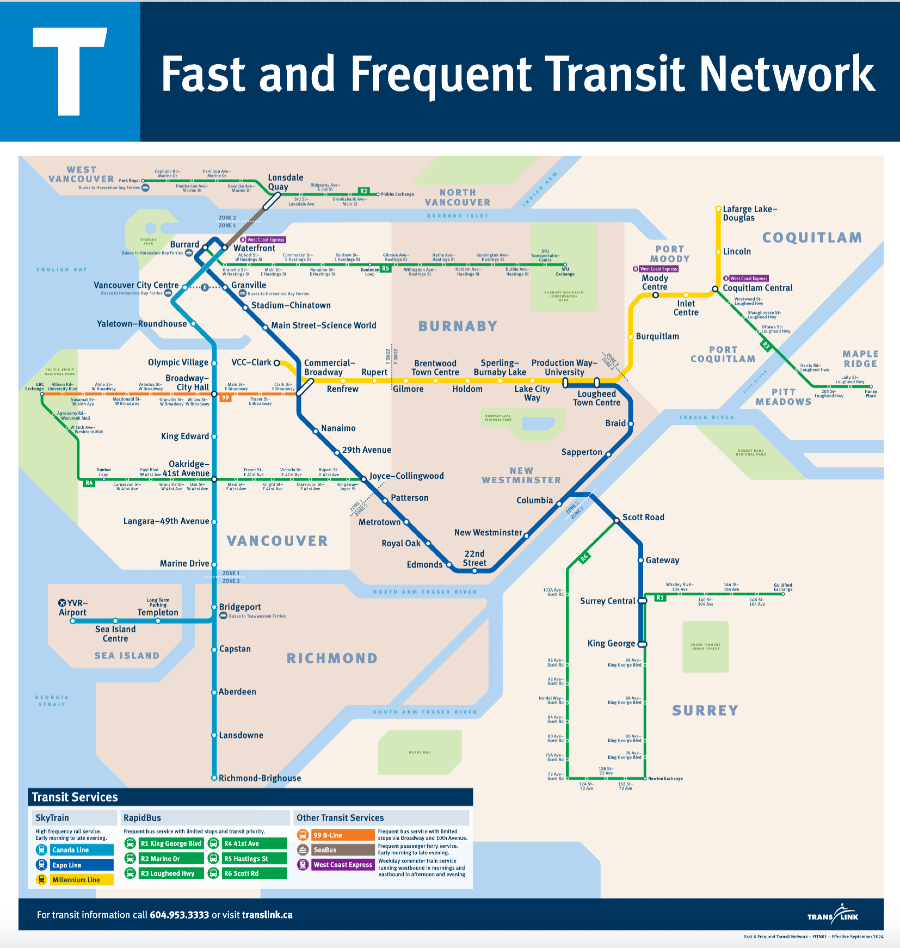

A couple of years back, I made the case that Vancouver qualified as "Canada's Best Transit Metropolis." It continues to beat 0ut Toronto, whose failures in building a transit network worthy of a metropolitan area of—what is it now, 7 million?—have been amply documented elsewhere. (Much of the blame can fall on Premier Doug and the late Mayor Rob, who deserve the opprobrium of all Torontonians for keeping a vast metro area stuck in last-century's gridlock. To quote the bard: Lord, Mr. Ford!) The city where I now live, Montreal, is hard at work on the Réseau express métropolitain, an elevated light-rail system that is already running driverless electric trains between downtown and the suburb of Brossard. The project has all kind of flaws, from lack of coordination with the existing transit network to frequent failures this winter, when—and who could have predicted this?—the temperature in Quebec dipped below zero. (On this count, the wisdom of the Montreal métro's original designers in putting every kilometre of track in the system underground has become manifest. For what it's worth, the REM team is promising this won't happen in 2026.) But, when it is fully built out to the west island, Trudeau Airport, and Deux-Montagnes, and if it can overcome its weather-related challenges, I predict the REM will turn Montreal, a city already well served by transit, into the place to beat in Canada when it comes to sustainable transport.

For the time being, though, Vancouver still has the lead. The good impression begins when you stroll, via open causeway, from Arrivals at the airport to the Canada Line, part of the (mostly) elevated SkyTrain system, which whisks you across the Fraser River to the Waterfront station, located in the historic Canadian Pacific Railway terminus, the end point of Canada's first transcontinental. Since it first opened in time for Expo 86, the system has continued to grow steadily (unlike Montreal's métro; an extension to the Blue Line is under construction, but the five new stations won't open until 2031), and now counts three lines, 54 stations, and almost half a million daily riders. The SkyTrain, which struck me as being no better than a glorified amusement-park people-mover when it first started to run, has evolved into a system beautifully suited to the geography, as well as the aesthetics, of Vancouver. Its high frequencies, up to one train every two minutes, keeps it comfortably uncrowded, and means you never have to run for a train—another one is always on the way. (The fact that you can pay your fare with a credit card is pretty great too. I loaded up my Compass card, as I usually do, but for visitors, this removes an impediment to hopping on transit; you can also do this in New York and London, and I wish Montreal and other Canadian cities would get to work on making this happen.)

The bus system has also evolved since I was a teenager riding aging Brill trolleybuses, which inevitably got bogged down among the cars. While the overhead wires are still there on many routes—clean hydroelectric power puts Vancouver's among the most low-emission transport systems in the world—riding a city bus is no longer an exercise in frustration. As I've written in previous posts, the network is extensive, with great coverage, the buses are comfortable and air-conditioned, and frequencies are impressive (the span of service, less so: Vancouverites go to bed early, and wait times at stops tend to get looooong after 9 pm).

On my most recent visits, I stayed at Wesbrook Village, a new neighborhood on the south side of the campus of the University of British Columbia—my alma mater—which is sited at the western tip of the peninsula of the City of Vancouver, just beyond Pacific Spirit Park, a preserved patch of old- and second-growth forest shot through with walking and cycling trails. There were bus stops right outside the door of my apartment complex, and others within a walk of a few hundred metres.