A Voyage Back to 1955, When Passenger Rail Still Ruled the Land

// After spending some time in Europe—where I almost always get around by rail, usually of the high-speed variety—I'm inevitably beset by a sense of melancholy when I return to North America. On this continent, passenger rail remains, for the most part, a disappointment. The inter-city networks are sparse. On-time departures and arrivals are the exception, rather than a strictly-observed rule. In too many places, the rolling stock is outdated (though Amtrak has lately been restoring services and modernizing its fleet, and, as I write in this post, about a recent Quebec City-Montréal trip, so is VIA Rail in eastern Canada). Trans-border services are inconvenient, with lengthy customs inspections. And travel speeds are achingly slow. Though the Acela in the United States's Northeast Corridor is sometimes called "high-speed," its average speed from Boston to DC is just 70 miles (113 kilometers) an hour; in most European nations, the Acela wouldn't even qualify as an express.

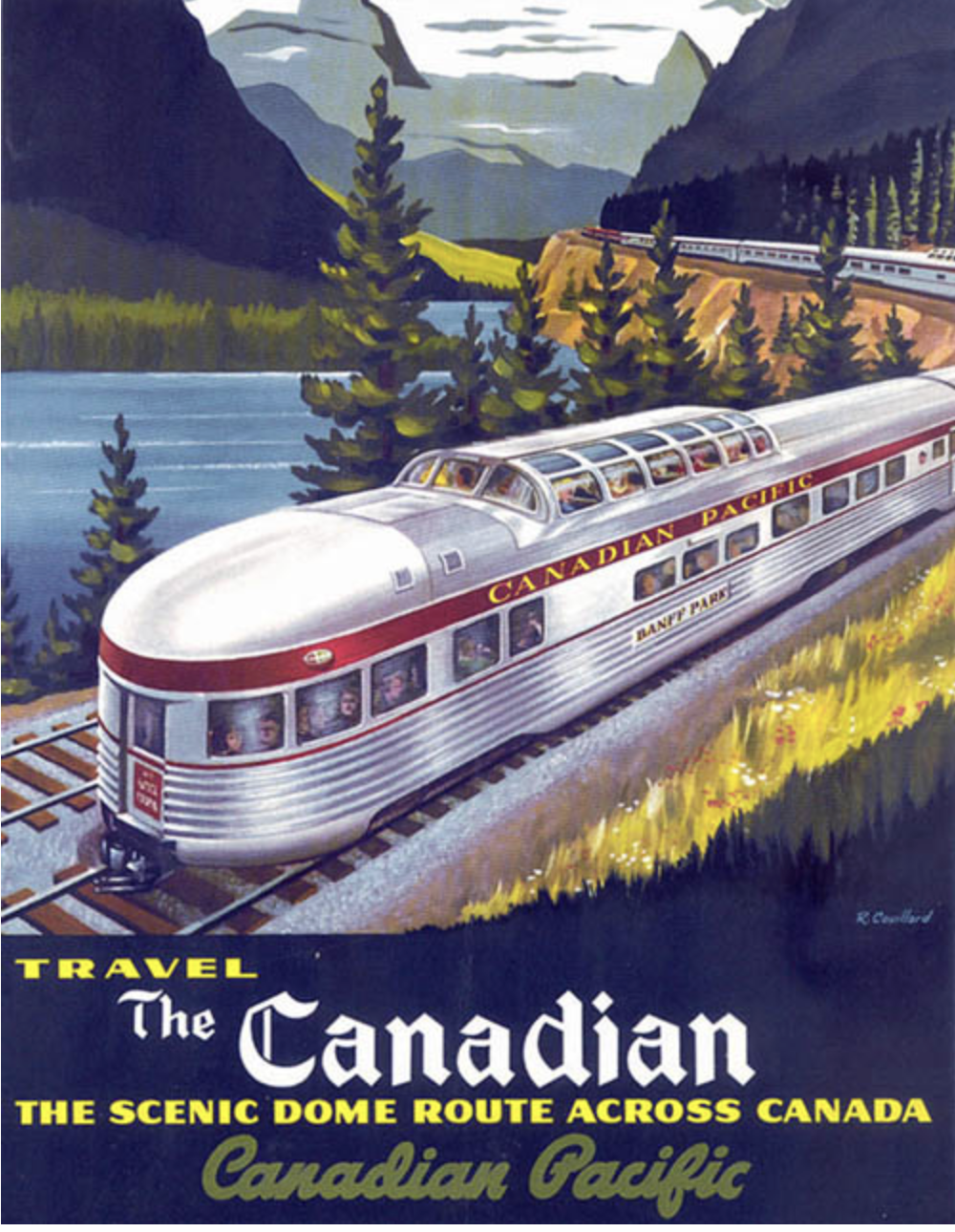

The temptation is to look to geography as the explanation for the gap between the quality, and quantity, of rail service on the two sides of the Atlantic. But even a passing knowledge of railway history makes it clear that blaming geography for the current dismal status quo is beyond simplistic. Over a century ago, American and Canadian trains had conquered geography, providing frequent, comfortable, and rapid service on many major corridors. The United States built the world's largest passenger rail network, with a quarter million miles of track, and at various times, Canada boasted the fastest passenger trains—steam or diesel—in the world.

Lately, when I'm looking for inspiration about what rail travel on this continent could be, I don't look to what's going on in France, or Spain, or Germany, or Italy. I look to what it used to be—and not in the distant past, but within the memory of many people alive today. More specifically, I look to the astonishing variety and high levels of service available during the 20th-century heyday of passenger rail in North America, circa 1955.

The secret to time travel, it turns out, involves getting your hands on a published railway schedule. I found one in a university library: a book with the odd title From Abbey to Zorra via Bagdad: Canadian Pacific Railway Passenger Services in the 1950s. (Abbey is a village in Saskatchewan; Zorra a municipality in Ontario; and Canada's Bagdad is located in rural New Brunswick.)

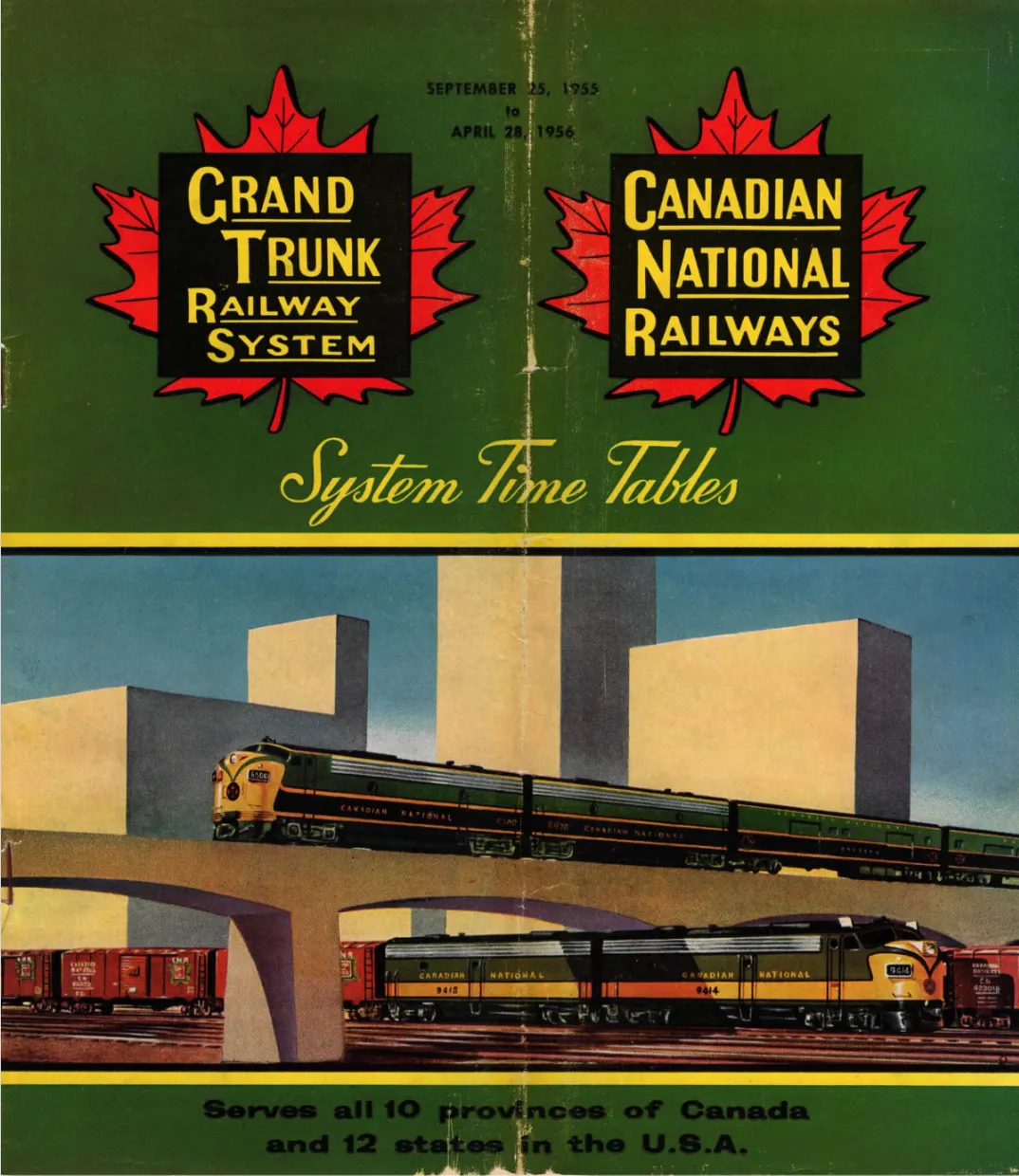

It was originally printed in 1980, by Sudbury, Ontario publisher Nickel Belt; clearly not an attempt to hit the bestseller lists, but a labour of love. A book like this is catnip for railfans, as worshippers of the iron road are known: there is page after page of black-and-white photos of tourist sleeping cars, stainless steel consists, wooden parlor cars, and RDCs (rail-diesel cars, self-propelled passenger cars that ran on many smaller lines), all diligently identified by manufacturer, line, and train number. The core of the book, though, is a reprint of the Canadian Pacific Railway's (CPR) brochure for 1955, complete with maps and timetables for services from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, to Victoria, British Columbia.

Turning to the pages devoted to Montreal, the city where I live, I experienced an immediate frisson—a shiver that mingled awe and envy. Now, Montreal today is not a passenger rail backwater, at least not by North American standards. I happened to ride the métro to the Central Station last week, and, in addition to commuter services to the suburbs, the destination boards posted trains to Quebec City, Toronto, and Canada's capital, Ottawa, as well as thrice-weekly trains to Senneterre and Jonquière in northern Quebec. Montreal remains a key stop on the "Corridor," which stretches from Quebec City to Windsor, across the border from Detroit, a strip that is home to about half of Canada's population. Those boards normally post departures for New York City—but, disappointingly, the Adirondack, the named train that runs down the Hudson River Valley to Penn Station, has been cancelled until further notice. (The issue is track maintenance on a 40-km [25-mile] stretch of Canadian National tracks north of the border, apparently—the latest news is that service will resume on September 8, 2024. For now, passengers have to ride a bus to Albany, where they can board an Amtrak train for the last leg of the journey to Manhattan.)

I've taken the Adirondack a couple of times, and it's a nice trip, but only really practical if you have a lot of time on your hands. Morning departure; at least an hour at the border as American customs officials wander the train, asking questions and inspecting baggage; followed by an evening arrival, which means you're not going to be checking in to your hotel until 8 pm. The last time I took it, the ride took 13 hours. You can get down there by bus or car in about six. Want to squeeze in a weekend in the Big Apple? Fuggedaboutit. On VIA/Amtrak, you'll lose two days getting there and back.

Now have a look at the schedule in 1955.