"General Motors Killed America's Streetcars"—Right? Not so Fast...

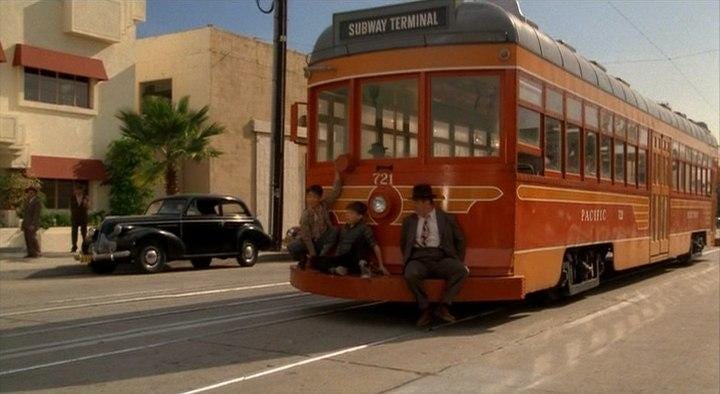

// Once upon a time, according to a persistent urban legend, Los Angeles was a tranquil constellation of residential villages on the Pacific shore, unafflicted by freeways, congestion, or smog. In the 1988 feature Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, an urchin asks gumshoe Eddie Valiant, played by Bob Hoskins, why he isn’t driving a car.

“Who needs a car in L.A.?” replies Valiant, as he insouciantly hops on the rear bumper of a passing streetcar. “We’ve got the best public transportation system in the world!”

The plot hinges on the dastardly plans of Judge Doom, who wants to pave over the animated denizens of Toon Town (which bears a marked resemblance to Watts) so he can build an empire of tire salons, fast-food restaurants, and billboards along a new kind of high-speed roadway: “Eight lanes of shimmering cement—they’re calling it a freeway!” Valiant reacts with disbelief. “Nobody’s going to drive this lousy freeway when they can take the Red Car for a nickel!”

This much is true: the Red Cars really existed, they really went everywhere, and the fare really was five cents. If you credit the Judge Doom version of history, a cabal of automobile interests tore up tracks in Los Angeles and across the country, and replaced efficient electric streetcars with polluting diesel buses in an effort to make the internal combustion engine the king of the road. This conspiracy theory, while it makes for compelling pop history, is at least a couple of notches too simplistic. The real story behind what happened to the Red Cars, and why Los Angeles has become a byword for sprawl and congestion, is a little more complex, but a lot more interesting.

Los Angeles owes its sprawled, horizontal form to railways, rather than freeways. Founded in 1781 as a New Spanish ranch town by mestizo and mulatto settlers, the city remained an obscure dot on the map until railroads brought a tidal wave of settlement from the Midwest; by the mid-1880s, fare wars between the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe brought the cost of a one-way ticket from Kansas City down to a single silver dollar. A railroad right-of-way to San Pedro, which became the city’s deep-water port in the 1890s, extended the city limits 20 miles southwest from downtown.

The building of the Owens Valley aqueduct—a story of civic corruption loosely told in Roman Polanski’s Chinatown—permitted the annexation of the San Fernando Valley, and the discovery of oil dispersed centers of industry, and population, throughout the Basin. By 1930, Los Angeles was the fifth-largest city by population in the United States—and the largest in area in the entire world.