First Nations are Righting the Wrongs of NIMBY Settlers, and Solving the Urban Housing Crisis, in the Canadian West

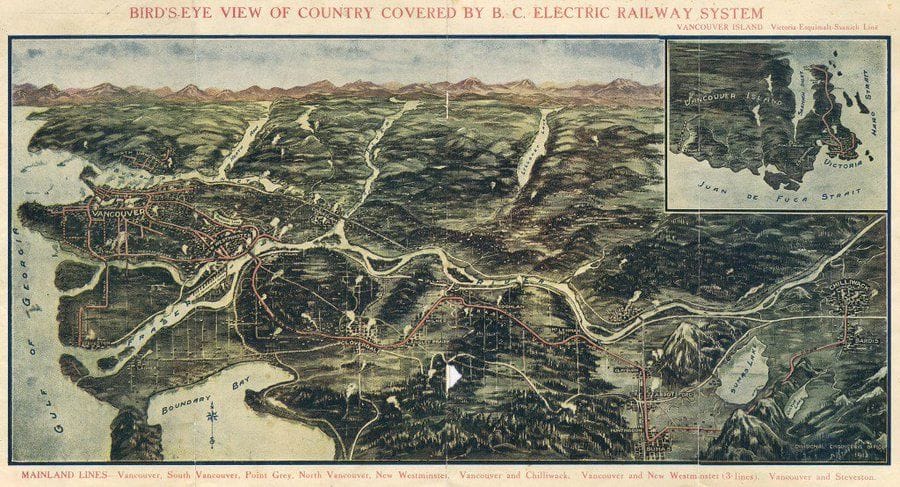

// I've been back home in Montreal for the last two weeks, but my thoughts are still in Vancouver, the city where I spent my youth, and where I still have family. As I wrote in the last HIGH SPEED dispatch, Vancouver has lately been excelling as a transit metropolis (that's especially true a North American context, where there isn't much competition when it comes to visionary transit planning; if Vancouver were a European or Asian city, it would fall in the middle of the pack). It's less of an inspiration as an exemplar of smart cycling infrastructure, which is a disappointment, given its—for a Canadian city—clement weather.

Though Vancouver has done really great work with its largely electrified bus network, boosting frequencies and introducing rapid and express buses that do a lot of heavy lifting, the real transformation has come thanks to the SkyTrain. This started as a rinky-dinky elevated line to carry crowds coming to Expo '86, but has since expanded in a very impressive way. (By the way, there's no shame in taking advantage of a world fair or other big international event to bring rail transit to a city: the first lines of the Métropolitain were built to serve Paris's Exposition Universelle of 1900, and, if all goes well, Los Angeles might have a high-speed rail line from Las Vegas in time for the 2028 Olympics.) Operating with headways as low as two minutes, and carrying half a million people a day, the SkyTrain network now has three lines and 54 stations, with 13 more under construction—which means Vancouver will soon have as many stations as the métro in Montreal, a much more populous city, which began building its network in the '60s, rather than the '80s. (Note to Montreal: Dépêche-toi, stie!)

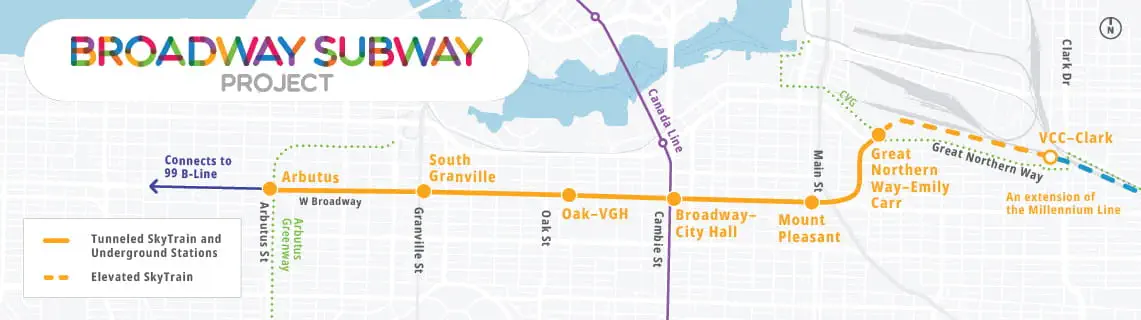

The next expansion of the SkyTrain is an extension of the east-west Millennium Line, which links the suburban city of Coquitlam to East Van. For the last few years, I've avoided travelling on the major thoroughfare of Broadway, because traffic is hopelessly snarled for much of its length thanks to construction of the extension.

Unlike most of the SkyTrain network, it will run underground (hence the name "Broadway Subway.") Due to open in 2027, it will link to the Canada Line—built for the 2010 Olympics—which connects downtown to Richmond and the international airport, and add six new stations to the network.

For the time being, the Millennium Line's western terminus is set to be Arbutus, a north-south avenue. From there, westbound riders will be able to board the 99 B-Line, which runs high-frequency articulated express buses, completing the run to the tip of Vancouver's main peninsula. It's an open secret that the next phase in development is likely to be a further extension of the Millennium Line all the way to the University of British Columbia, which, in addition to 60,000 students, is also home to new high-rise residential neighborhoods such as Wesbrook Village. That kind of demand-driving density makes it a perfect anchor and terminus for a mass transit line.

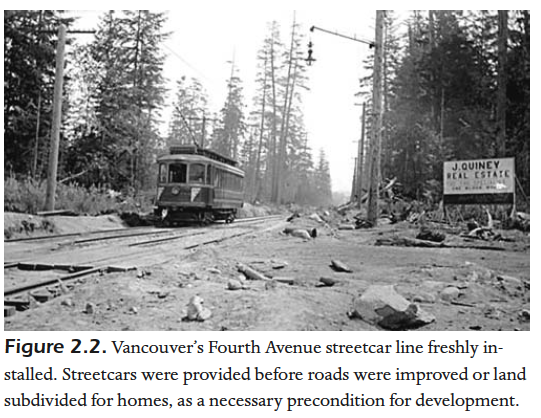

What's puzzled me is what's going to happen with the seven-kilometer stretch that will separate the Arbutus station and UBC if and when the extension is built. Density along the corridor is extremely low—in fact, it epitomizes the worst features of Vancouver's urbanism. Now, I grew up in this area, and, in many ways, it was an idyllic place to spend a childhood. Leafy streets, proximity to old-growth forest in what was then called the University Endowment Lands (today's Pacific Spirit Park), lots of small parks.