// I'd wager that the most impressive—massive, powerful, even awe-inspiring—piece of transportation technology most people are likely to get up close to these days is a full-sized passenger train. Cars, especially the way we build them today, can be big chunks of machinery, but even a Hummer or a Cybertruck has to be right-sized to negotiate city streets and highway lanes. Passenger jets are massive, especially long-haul Airbuses and Boeings, but these days we are cut off from their true scale: passengers almost always approach them through the long, isolating corridor of the jetway.

A passenger train is different. In most stations, you can still walk up to a locomotive on the platform, and feel the contained power of a 4,200-horsepower diesel engine, or a power car drawing electricity from a 25 kilovolt overhead wire, as it towers over you, waiting for its chance to be unleashed. For the 98 percent of North Americans who have never boarded an inter-city train, the first encounter with a real-life locomotive can be eye-opening.

Even locked up in museums, locomotives have the power to awe. Over the years, I've seen several of the most important passenger trains in history in rail museums. I'm thinking of the O Series Shinkansen, the world's first true bullet train, at JR East's Railway Museum in Saitama; the gorgeous, "garter"-blue Mallard at the UK's National Railway Museum in York, which set the world speed record for a steam train (126 miles-203 kms-per hour, in 1938); the Royal Hudson, the steam engine that pulled Queen Elizabeth across the Rockies in 1939, at Exporail just outside my hometown of Montreal; and the collection of pioneering mountain-conquering trains and funiculars that I describe in this visit to Switzerland's Verkehershaus.

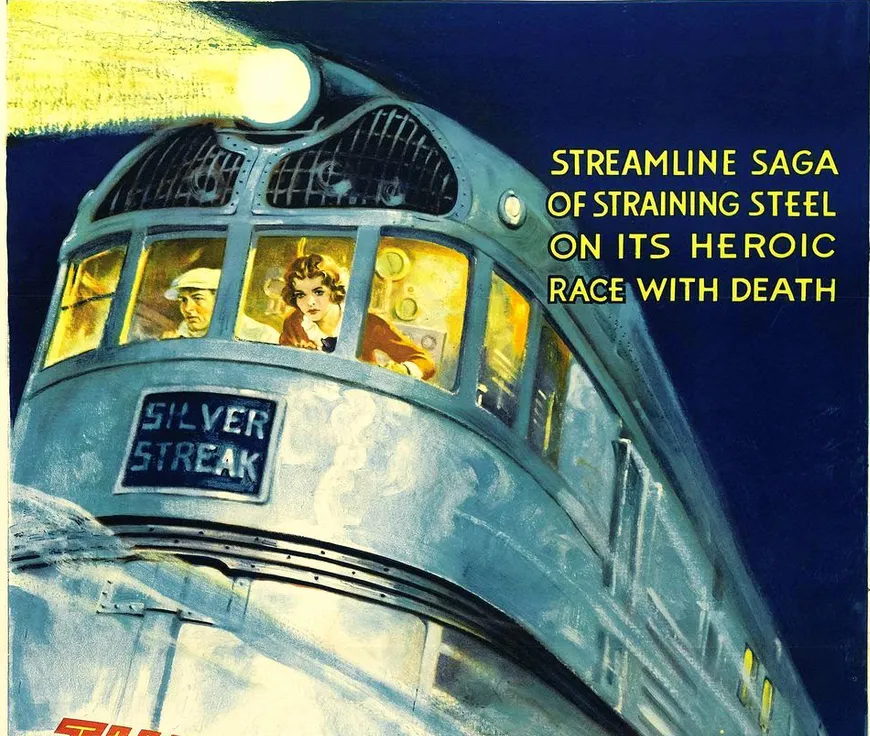

But I can't think of a train that had me more mesmerized than the Pioneer Zephyr, which I encountered in all its shiny, streamlined, shovel-nosed splendour at the Kevin C. Griffin Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, Illinois.

The utilitarian name undersells just how impressive an institution this museum actually is. This place sprawls: it is the largest science museum in the western hemisphere (and keep in mind that this hemisphere is home to The Smithsonian). How big is it? 400,000 square feet of exhibition space, housed in the Palace of Fine Arts from the 1893 World's Columbian Exhibition (readers of Erik Larsen will know it as "The White City"), which sits on fourteen acres of Lake Michigan shorefront. This is a museum that contains a full-sized Boeing 727, a German U-boat captured in WW2, a four-storey tornado in constant motion, a working replica of a coal mine, and several cobblestoned blocks of a frontier town—and still has room to spare.

You don't even need to pay admission to experience the Pioneer Zephyr. Acquired by the museum in 1960, it was for years housed outdoors, where it was exposed to the (merciless) Chicago elements. More recently, it was cleaned up, brought indoors, and is now on display on the lower floor of the museum's atrium, not far from the ticket desks. On my visit, a class of elementary school students was running rampant through its cars; I let them have their deafening way with the old girl before I began a leisurely stroll through her cars.

Even today, this is one radical-looking hunk of train. Gazing at its gleaming, slant-nosed, rather intimidating profile, several images came to mind: the helmeted head of the hero of RoboCop, the cyborg in The Terminator stripped down to its metallic skeleton, or a Norseman in full battle armour.